Open Learning Design in Context: Expanding the Continuum

Authors:

- Verena Roberts, Thompson Rivers University

- Michelle Harrison, Thompson Rivers University

Introduction

As open-learning designers, we strive to integrate open educational practices (OEP) in all projects that we are invited to collaborate with. OEPs have been broadly defined and include multiple elements of teaching and learning, such as participatory and critical pedagogies, the use of open licensing and open technologies, the development and adoption of open educational resources (OER), and collaboration with and recognition of multiple voices and perspectives (Tietjen & Asino, 2021). The responsive, contextual, and personalized nature of each person’s open learning awareness and readiness makes open learning design a complex challenge in any learning environment. As Cronin (2018) highlights, “Openness is not a one-time decision, and it is not universally experienced; it is always complex, personal, contextual, and continually negotiated” (p.291). This points to a need to create a supported ethical journey to openness for learning design professionals, instructors, and learners, and in the design and learning process, providing choices around when open approaches might be appropriate, how and when to openly share resources and practices, and guidance and resources about privacy, risk, and the increasing role that technologies play in surveillance and digital monitoring.

Though there is not one overall definition of Learning Design, one way that it can be understood, is as an explicit framework for describing a range of teaching and learning activities with a goal of improving student learning. Learning designs (as products) allow educators to represent, re-use, share and discuss their understandings of the tasks, tools, and intended pedagogical outcomes of a planned learning experience. Rather than describing one open-learning design precedent (Gray, 2020), this blog post examines how we might start to build a learning design framework that can help guide educators on an ethical journey to include more open approaches. Our overall question is:

- How can we scaffold design decisions that are tied to personal contexts, but that include design principles that could lead to more equitable, accessible and responsive learning environments for all learners?

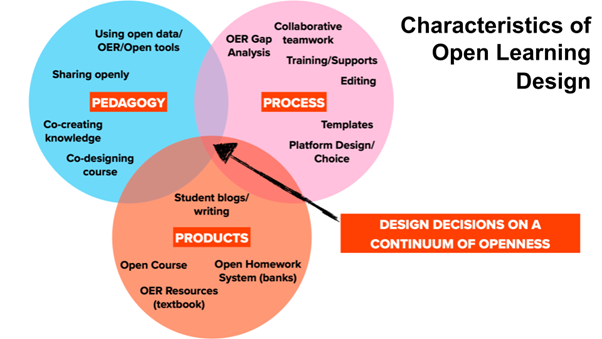

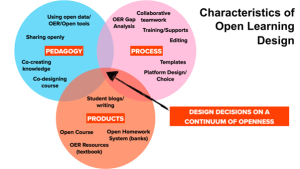

We have been examining a variety of cases to look for emerging features that support open educational practices and have developed a conceptual model that includes three key elements (themes) that we feel underpin open learning designs. Our early ideas are captured in the Open Learning Design Continuum (OLDC, Figure 1), an ever-changing and evolving collaborative learning design model that examines the potential principles of open learning design in multiple higher education contexts. In a comparison of case studies of open curriculum designs at two Canadian HE institutions, we continue to examine ways that educators and learners have experienced a variety of approaches to open learning design, including the blurring of informal/formal spaces and the uses of open educational resources (OER) and open platforms to create more student-centered, equitable and accessible learning spaces.

The OLDC Model–Ethical Considerations

When considering the possibilities for defining open learning design, there are many potential characteristics and considerations, which are always contextual and need to balance a variety of perspectives including privacy, values, epistemic agency and pedagogy. This leads us to ethical tensions in our work, as decisions around how openness is enacted in the teaching and learning space is not neutral. When we introduce open approaches, be it introducing an OER, an element of open pedagogy, implementing open collaborative teamwork or open digital tools, we know it can also introduce barriers or challenges. This blog post highlights an attempt to examine the characteristics and themes that distinguish an ethical open learning design from other instructional design templates.

One example of an ethical tension is that one of the tenets of OER use is the reuse and sharing of resources. We recognize that as everyone engages with open practice in their own context that they may only be ready to adopt an OER, so at this stage of their own journey, the spirit of reciprocity and building of the knowledge commons may be missing. From a sustainability perspective, there is a requirement to constantly update materials, and the labour involved in adapting and creating OER can be substantial and is often supported through one-time grants or done “off the side of the desk”. As we encourage teams to move towards a reciprocal relationship and deeper engagement with open approaches, how do we ensure they are supported and have the means to continue to build their open practice?

We need to consider a variety of contexts, platforms, mediums, perspectives, timing, flexibility, and approaches as we incorporate a continuum of open design decisions. We hope that by identifying the design principles that support open approaches we can create a shareable design model that can be used by teams to help support ethical decision-making about various elements of open educational practices.

Based on experiences as learning designers working in open contexts and with support from the literature, our initial thoughts are that open learning design occurs on a continuum that includes the following elements of OEP (see also Figure 1.0):

- Process: The process of working together collaboratively, (reflexively), and openly on the design

- Products: The final learning product(s) from the collaborative development process is shareable (could be a resource, a fully open course, or elements of courses (e.g., H5P files, WebWork questions)

- Pedagogy: The intentional design includes some aspects of open pedagogy such as participatory technologies, people, openness and trust, innovation and creativity, sharing ideas and resources, connected community, learner-generated, reflective practice, and peer feedback. (Hegarty, 2015; Tietjen & Asino, 2021)

We recognize that there are multiple continuums and mixtures of all three elements that designers and team members bring to each project. We hope to use it as a starting place to help frame design team discussions around practices and ways we work together.

Figure 1 demonstrates some characteristics that might be included in each element.

Figure 1.0. Sharing the Many Ways to Design for Open Learning. Open Education Conference. CC BY Smith, Harrison & Roberts (Oct. 17, 2022).

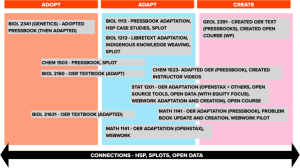

The OLDC was inspired by the variety of perspectives and approaches to open learning design that were revealed during the development of a Zero Textbook Cost (ZTC), Associate Science Degree program at Thompson Rivers University. Within each unique course project, the open learning design approach helped to identify the key intentional design choices (Adopt, Adapt, Create and/or Connect) made in collaboration by the design project teams when considering the use of open educational resources and/or practices. These initial ZTC project comparisons inspired the team to consider other open learning design examples that highlight students as co-creators and co-designers of open learning design projects in undergraduate programs at TRU and graduate courses at UCalgary.

OLDC currently uses four intentional focus areas to help compare and contrast the multiple open-learning design approaches using Open Educational Resources (OER) and/or Open Educational Practices (OEP).

- ADOPT an already-created OER

- ADAPT an already-created OER

- CREATE an OER

- CONNECT and expand upon OEP

Figure 2.0. A continuum of Openness. Open Education Conference. CC BY Smith, Harrison & Roberts (Oct. 17, 2022).

In our ZTC project we saw a variety of ways that the OLDC was enacted. In Figure 2 above, we have mapped the many course development projects onto the continuum of openness, from ADOPT to CREATE (with CONNECTIONS woven throughout each). One of the early courses (BIOL 2341) saw the team adopting an OER (pedagogical), using some open process (shared templates, collaborative teamwork, an OER gap analysis), but did not have students or users creating or using open artifacts. However, on a subsequent course development project (BIOL 1113), the course author moved towards more open approaches, including adapting OER, adopting open pedagogical approaches (open student collaborations in SPLOTs, H5P case studies), and moving towards a more open collaborative process.

The potential personalized and contextual design variations not only present unique opportunities for student-centred learning. They also provide ethical challenges in terms of equity, inclusiveness and accessibility. We look forward to examining the potential ethical strengths and challenges that open learning design affords instructional designers, educators and students.

References

Dalziel, J., Conole, G., Wills, S., Walker, S., Bennett, S., Dobozy, E., Cameron, L., Badilescu-Buga, E., & Bower, M. (2016). The Larnaca Declaration on Learning Design. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1(7), 1–24.

Gray, C. (2020). Markers of quality in design precedent. International Journal of Designs for Learning, 11(3), 1-12.

Cronin, C. (2018). Balancing privacy and openness, using a lens of contextual integrity. Proceedings of the Networked Learning Conference, 2018.

Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology, 4(4), 3–13.

Roberts, V., Havemann, L., & DeWaard, H. (2022). Open learning designers on the margins.

Tietjen, P., & Asino, T. I. (2021). What Is Open Pedagogy? Identifying Commonalities. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 22(2), 186–204.