A Framework and Model for Engagement in Open, Online Spaces

Authors:

- Michelle Harrison, Thompson Rivers University

- Michael Paskevicius, University of Victoria

Acknowledgement: Dr. Irwin DeVries, Dr. Tannis Morgan, and Tom Woodward were major contributors to this project and part of the design team.

Introduction

This design case outlines the development of an open resource, including a software application and reflection framework tool, that explores open and critical approaches to learning and instructional design. Our team included four educators who teach and have learning design backgrounds. We started this project as we were questioning how the shift to more open approaches to education requires a change in epistemological and pedagogical practice. We noted that contemporary resources and educational tools continued to be based on traditional, systematic, and static approaches to knowledge that could not meet our design needs and pedagogical intentions. For example, the traditional textbook format, even when offered as an open educational resource, can lack the interactivity, agency, and accessibility needed to enable spaces that honor multiple voices and perspectives. Our goal was to support co-created knowledge and to challenge traditional roles and hierarchies afforded by open pedagogical approaches.

In light of these challenges, our project had two overall goals:

- The first was to develop a reader/resource in critical learning design that we initially termed the “Untextbook”, based on the principles of open pedagogy, including participatory technologies, knowledge sharing and co-creation, and open, connected communities (Hegarty, 2015).

- The second was to develop not just a content resource (or book) that could be used by students and practitioners, but also a tool that could model and include pedagogical approaches that are more inclusive, participatory and open.

In this short post about our design, we will briefly outline some of the design decisions we made including:

- gathering feedback on expanding our notions of the textbook and open resources,

- using this feedback to work with a developer to embed the principles into a resource and platform,

- working with contributors to build contributions and provocations that might lead to deeper engagement,

- developing a framework for engagement with participants within the resource,

- piloting the design and gathering feedback from students.

Rethinking the Notions of a Textbook

Our first step was to gather feedback from other educators, and we engaged in various sessions at conferences, gathering artifacts and input. Figures 1-3 outline questions and capture feedback in a visual recording. At this stage of the project, we were still thinking of this resource as an “Untextbook” as we tried to interrogate the notions of how traditional structures, still embedded in our open tools, influenced our pedagogical decisions and resulting practices, often enacted through hierarchical digital spaces.

Figure 1: Questions for feedback (Used to gather stakeholder feedback at several conferences)

While gathering the feedback from conference attendees based on the questions in figure 1, we had a visual designer create sketchnotes capturing the process and feedback. These visualizations are represented in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2: Graphic recordings of Cascadia Summit [will add to one figure in blog post)

Figure 3. Brainstorming for a multi-layer narrative form of a textbook with non-linear structure

Developing a Platform

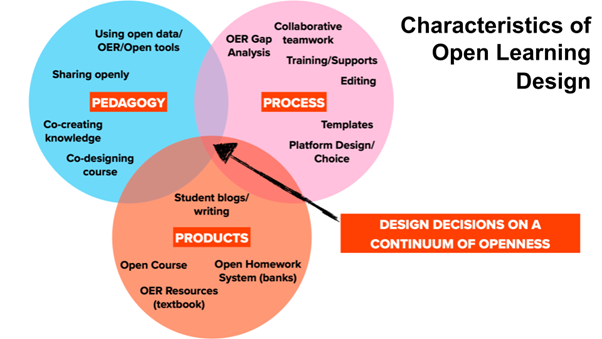

From our initial engagement with our open community, five overall attributes emerged as a useful starting point to center equity-centered learning design in a digital resource, including interactivity, agency, accessibility, structure, and voice. Our challenge was to consider the ways that we could incorporate these attributes, including elements of open pedagogies, knowledge sharing, and co-creation, critical approaches, and the creation of open, connected communities (Hegarty, 2015), which could be built into a digital online space.

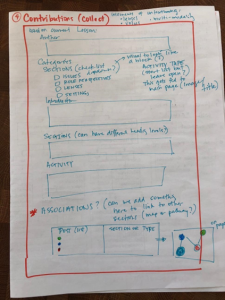

As we explored the possibilities and constraints of the various platforms, our colleague and web developer, Tom Woodward posed many challenging questions. As a team, we discussed technological challenges and ethical dilemmas for work in the open. While we all embrace the benefits of open pedagogical practice, we recognize that openness introduces other ethical tensions around ensuring safety and privacy for learners. There is also a tension between creating a space that has structured connections versus one that is completely open, but which might become chaotic and unnavigable. Through multiple sessions with Tom and our team, we landed on a customized WordPress theme that allowed for simple authoring, non-linear organization and multiple-entry points, and a variety of choices around open licensing. Figure 4 shows an early hand-drawn storyboard for one of the pages, and a team member’s notes on the types of design choices we were discussing.

Figure 4: Storyboard and design notes for open platform development

“Contributions or collections or constellations: This is based on the “lesson” format that in the data praxis site. We talked about this being a form that would be more SPLOT like in that it would not need a login (Tom had shown us a form he used on a different project that would allow for this, I think). Authors would identify the “SECTIONS” they are addressing (perhaps from a checklist) and then choose the Activity Type. Likely we would need a spot where they also identified the chapter this post was associated with. They could then fill in the various sections (text, media, or activity) by responding to the original chapter. We may want more blocks on this (similar to the chapter with complementary resources or further readings (or references?). I wondered if we wanted to add another “pathways” block…where the contributors could create a map/visual link to other related posts? This might be too complicated though.” (notes from planning documents)

Learner agency, multi-vocality, and non-linearity were key principles for the design of the resource. The platform allows for the ongoing building of resources and learner ownership/authorship, content and contributions can be reorganised into new configurations and iterated, authoring can be open/anonymous or other, and the simple authoring tools embedded directly in a page will allow students to choose different lenses and approaches. We also considered how to create an invitation to contemplate contested knowledge and invite multiple layers and perspectives.

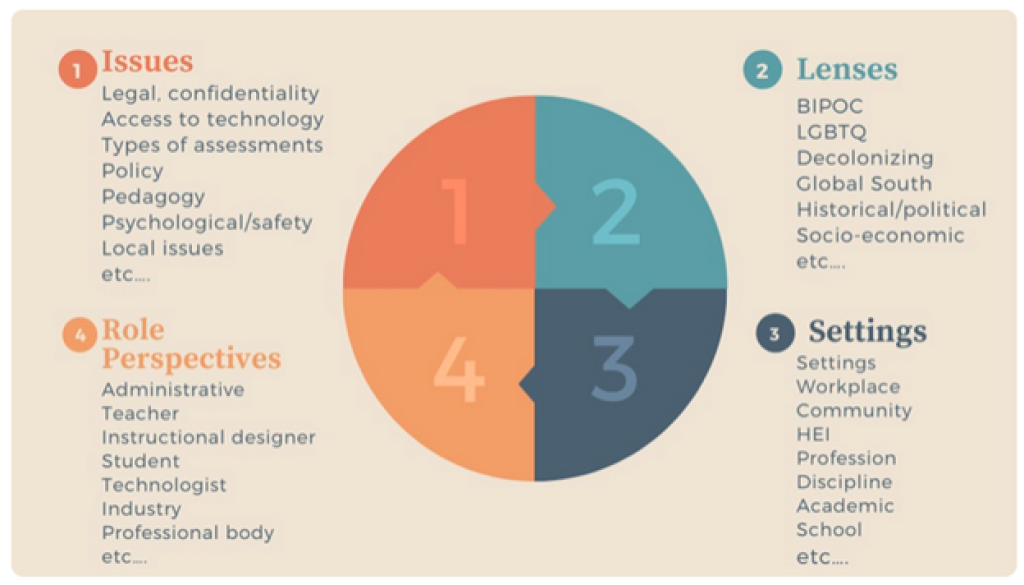

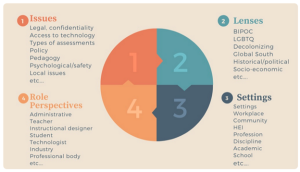

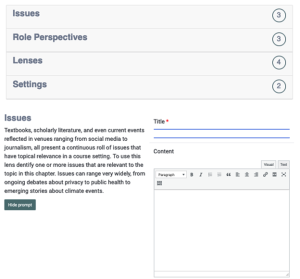

One design decision was to confine the intended use within an educational setting that includes responsible and accountable moderation, setting appropriate boundaries for debate, including a focus on equity and respect. As we considered how this “untextbook” might be used, we felt that some pedagogical structure might be helpful and developed a reflective practice framework that provided guidance around participatory interaction with the content, which would help learners honor multiple voices and lead to a shift in perspective. In our conversations about how to build this element of scaffolding into our activities, it became a central feature, and Tom was able to incorporate it directly into the WordPress theme (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Reflective practice framework for engaging in activities, embedded directly into WordPress with simple authoring tools and scaffolding. Practice Example: Managing Change Activity.

Call for Contributions and Resource Development

We embedded our design principles into the call for proposals, outlining the focus in the background and aim and scope, encouraging multiple modalities, embedding the reflective practice framework directly into the contributions guidelines, and into the peer review criteria and process (open peer review, emphasis on inclusion and diversity). The current iteration of the resource “Rethink Learning Design” is openly licensed, has 12 chapters and two practice examples (with student voice contributions see Figure 6). One of our goals was to create a shareable template for the resource design, so other educators, from various disciplines, could adapt and use it in their own contexts.

Figure 6: Screenshots of the Rethink Learning Design resource, outlining a non-linear organization of contributions

Design Questions

As we continue to implement this resource in educational settings (two courses in a graduate program) we encounter further design questions. How will we manage the content that is developed and how do we keep it manageable for users and readers? After three years of testing activities participants have shared that the amount of content already developed can be a bit overwhelming. They share that they appreciate seeing content from past learners but wonder how to engage with that past content. We had also hoped for a more visual way for participants to chart their own pathway through the contributions, through a visual constellation, and to build the student voices contributions into chapters that can then be iterated on.

References

Harrison, M., Paskevicius, M., Devries, I., & Morgan, T. (2022). Crowdsourcing the (Un)Textbook: Rethinking and Future Thinking the Role of the Textbook in Open Pedagogy. The Open/Technology in Education, Society, and Scholarship Association Journal, 2(1), 1–17.

Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology 55(4), 3-13.